NASA’s Apollo Command Module Mission Simulator

I was only seven when Apollo 11 landed on the moon. Like most of my friends I was very interested in anything to do with space. I read comic books and watched Lost in Space, Star Trek and whatever cheesy science fiction movie aired on TV. Every now and then my dad would bring me to work with him. But for me, the “outer space” associated with NASA and the “outer space” I would see in science fiction were two different things. One was bleak and sterile, the other was full of adventure. Apart from seeing rocket launches or visiting the museum exhibits, visiting NASA was about as much fun as visiting an oil refinery.

When I was 14, I went to a local movie theater to see a screening of the Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. I had a vague memory of the movie when my parents took us to a drive-in to see it in 1968, but I was way only six at the time and way too young to understand any of it. Our local cinema was screening it for one weekend only so this was my chance to see it (back in 1975, before there were movie rentals or Netflix, the only other way to see a movie after it finished its initial run was if it happened to be rerun on TV). By the time the movie started there were only about a dozen other people in the theater and I wondered if had just wasted my two dollars. But by the end of the movie I was overwhelmed.

I didn’t know it at the time but 2001 would haunt me for for most of my life. Its initial impact on me was that this was the first work I had ever seen that depicted space travel authentically. Here was the bridge between the concept of space I associated with NASA, and the “space” depicted in sci-fi. Over the years I gradually became aware of its other important aspects. Part of the genius in 2001 is the element of design. Envisioning a world 33 years into the future meant envisioning the future of industrial design, graphic design and even user interface design. Rather than the trope of panels of blinking lights, real effort was put into speculation about future technology and it resulted in an uncanny prediction of our present day world.

I instantly became obsessed with the movie. I read the book, and every other book by Arthur C. Clarke. I learned about how the movie was made, including the special effects and concept art, which ultimately led me to the artist who created the iconic image for the movie’s poster, Robert T. McCall.

McCall’s work chronicled the dawn of manned space flight the way Norman Rockwell captured the American experience. I grew up with his artwork and never knew it. McCall’s artwork appeared in National Geographic, Time and Newsweek magazines. His paintings of Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz were made into postage stamps. His monumental mural depicting man’s achievements in space appears in the Smithsonian Institute’s National Air & Space Museum.

Book cover image for Our World in Space. Credit: Robert McCall

In the 1970s there was no internet so being able to find out more about McCall’s artwork wasn’t easy. Neither the public library or high school library had much. On a random visit to a bookstore at the mall, I found a large book of McCall’s artwork titled, Our World in Space. With text written by Isaac Asimov the book was a hefty $80– too much for a high-school sophomore who earned most of his money mowing lawns for $6 a piece. I was too young to drive but I would hitch a ride to the mall with my older friends and visit the bookstore whenever I could, just so I could look at that book. Eventually my friends all chipped in and bought the book for my 16th birthday.

During the last semester as a high school senior, I was still somewhat undecided about what to study in college. My parents knew I wanted to study art, but had no idea about how I would make a living at it. My dad urged me to study computer programming which was something else I was really interested in, but wasn’t very good at it. At the time my future seemed abiguous. Then one day a friend called to tell me that Robert McCall was painting a massive mural at the Johnson Space Center (JSC). I bundled several of my drawings and paintings into a cardboard portfolio and drove my mom’s car over to NASA hoping to meet him.

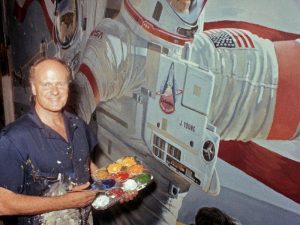

Robert McCall in 1979 painting Opening the Space Frontier, The Next Giant Step at the Johnson Space Center. Credit: Robert McCall

I walked into the Visitor’s Center at JSC. Inside the exhibit area, the long, three-story wall outside the auditorium was obscured by scaffolding and plastic drop cloths. I walked up to the information desk and asked the woman there if it was possible to meet the artist painting the mural. She smiled and said, “Of course.” and walked me over behind the ropes. Amid the maze of scaffolding she yelled up, “Mr. McCall? You have a fan who would like to meet you.” I looked up to see someone near the top peer down over edge and reply, “Sure, send him on up!” With my portfolio tucked under one arm I climbed up several ladders until I got to where he was working and introduced myself. He spent about two hours that day looking at my work and talking to me about his career. He had flown bombers in World War II training bomber pilots and where he began creating paintings of military aircraft. During the 1960s’ he documented a lot of the space program in his work and was given extraordinary access by NASA to during missions.

Robert McCall was extremely generous with the time he spent with me. He was encouraging about my artwork. He invited me back to have lunch in the JSC cafeteria with him on other days where we talked at length about the future and more about his work. On another visit I sat as a model for one of the smaller figures in the mural. While I was sitting there I told him that my parents were uneasy about me pursuing art as a career. Confident in my ability, he told me to tell them not to worry and urged me to continue with it. After I got home I told my parents about his advice and from that moment on they never doubted my career choice.

The last time I saw Robert McCall was the day of the dedication of the mural. To kick off the ceremony he was to give a presentation showcasing his artwork in the JSC auditorium. I went up to the projection room where he was sorting through the slides he was going to show. I had the book my friends had bought for me a couple of years before and asked if he would sign it for me. He took the book and walked off to another table to sign it. Meanwhile, I busied myself looking at all the slides of his work on the light table. I couldn’t imagine one person producing so much work. About 20 minutes later he handed the book back with an elaborate drawing covering the endpapers inside the front cover, with the inscription, “To Chris, Best wishes for a Fantastic Future, Robert McCall, 1979”.

Over the years I would write to him from time to time. I would keep him updated on what I was doing. By 2000 I had been working as a 3D illustrator and just completed a poster where I created a futuristic version of the Houston skyline set several hundred years in the future. In the illustration there was a floating satellite city which was a direct reference to a theme in many of his paintings. I mailed him the poster with a note thanking him for the inspiration. He mailed me back thanking me for the poster and asking me how it was done. In 2010 I found out that he had passed away earlier that year. I wrote to his wife to express my condolences and wanted her to know how much he and his work meant to me. She wrote back thanking me for the note and explained that it meant a lot to receive it. She also said that she received dozens of letters like mine from others who he had inspired in much the same way.

I still have the book he autographed for me. Long-since tattered and worn, it remains one of the things I treasure most.